Sustainability & partnerships: Dan Lapid (Centre for Advanced Philippines Studies) interview

Diving back in history

WASTE and its partners around the world have been changing the development game for nearly 4 decades. We have together developed sustainable and inclusive solutions to many challenges in the waste management and sanitation sectors. Approaching the organisation’s 40th anniversary, we wanted to revisit some key players from our history of collaborations to learn lessons on how we can maintain the spirit of our founders and early work as we move forward.

The following traces WASTE’s history through three continents and many decades, sharing the stories of 7 pivotal individuals who have contributed to this spirit through our work together. These individuals and organisations have continued to share our spirit of inclusivity in everything they do.

A few key takeaways

- Through our holistic approaches, WASTE and its partners around the world have been working on the underlying concepts of ‘circularity’ for decades. It is only recently that high level discussions have rebranded and called more attention to the importance of what is called today “circular economy”. Circularity is integrated in our approach.

- Working with the informal sector is difficult but a critical component to sustainable waste management systems. All our partners echo that this aspect of the work as pivotal to the inclusion and innovative nature of their work.

- Institutionalisation of key concepts and approaches in policy, whether on local or national scales, are crucial for ensuring sustainability of our work.

- Buy-in from the communities, especially local leaders, can either catalyse the success of or be the sole reason for failure of interventions. We must ensure our programmes and solutions are co-created with and by the communities we are trying to serve.

- Real change and local ownership take time to have sustained impact. Our projects, ambitions, and relationships with key stakeholders, shouldn’t forget this key consideration.

Gamechanger 7: Dan Lapid

Executive Director, Centre for Advanced Philippines Studies (CAPS)

Manila, Philippines

1. What sectors were you working in, and can you describe your journey with WASTE?

The Centre for Advanced Philippines Studies (CAPS) was focused on research, with a vision to help the government analyse things. During those times, the Philippines was recovering from the effects of martial law, and we wanted to help. CAPS was like a think tank working on economy, politics, governance, and environment.

It was in the early 1990’s when we got to meet WASTE. After that, our work became more focused on waste management. In the early ‘90s, we were doing documentation research for the UNDP, World Bank, etc. on recycling and composting. We were part of the UWEP programme, and then there was UWEP 1, 2 and UWEP+. After this there was the EcoSan (Ecological Sanitation) ISSUE 1 and 2 projects. So that is how we started together. We were doing research on urban environment, specifically on solid waste management, and then later when UWEP and ISSUE came we also did projects on the ground. We worked with WASTE’s co-founder, Arnold, who was a very professional and good man, and I learnt a lot from him. He was very kind and generous with his time and knowledge.

2. Can you share a little more about the projects?

The Issue project was on ecosan, but the UEP programme was on solid waste. WASTE was able to acquire projects funded by the Dutch government. Issue and UEP both were funded by the Dutch government and it was WASTE that conceptualised the whole programme, and since they knew me they got me as a partner in the Philippines. To implement the programme. Thus we diversified the focus of work being at our organisation from research to also implementation partners on the ground. The model that we were using for the projects was the ISWM model primarily.

3. How did you work on the ground in these projects?

Before CAPS, I was working in the private sector. I do not have a degree in Environmental Science, I am sociologist. So the Integrated Solid Waste Management (ISWM) concept, approach and the technology were really new to me. I was really learning on the job and I learned a lot about the urban environment, integrated and sustainable solid waste management and such things. I can, to an extent, also say that because of my engagement with WASTE, I sort of became very environmentally conscious. It came that people started to call me an environmentalist. So the environmentalist piece and approach that I developed throughout my engagement with WASTE carried with me through the work I did over the years. People were noticing it until 2014-15 when we eventually closed the organisation.

4. Did you face resistance to the way of working the ISWM promoted?

Prior to the year 2000, integrated sustainable waste management was only in the minds of a few. Very few people were focused on recycling, composting, etc. It was not in the popular mindset. In the UWEP project, we did the promotional advocacy and also networking with many organisations and the government. Somehow, we were able to generate interest. We were able to connect and identify the players such as the formal and informal organisations and link up with them. This, in turn, became beneficial as we were able to develop our own network to sustain us later. As it became more popular in the minds of the people, in 2003 Philippines adopted a law on ecological solid waste management and we were a part of the network that assisted the legislative congress to craft the law.

5. How was the law developed, implanted and enforced in the Philippines?

The law was enacted in the early 2000’s but implementation was very difficult. Everybody was experimenting with setting up the segregation and putting up material recovery facilities and other such infrastructures on the ground. While the Department of Environment was very supportive, there were still concerns that would arise from the other departments and branches of the government. Many things were achieved in terms of segregation, where a lot of dump sites were closed or transformed into segregation centred where they would tap methane gas out of it to produce electricity. So there are many positive movements, but still there is still more to be done.

6. Can you share some challenges encountered in the work?

The biggest challenges that we encountered during the implementation of the programme was not just the government bureaucracy and the system, but also the local people. Many times the people themselves would not cooperate. It also depends on the mayor and the local chief, if they are aggressive in implementing change, then the local people follow. Otherwise, it is very difficult. You need these local champions for people to look up to and follow in order to implement and adopt such practices on the ground.

There are many civilian champions such as students, religious figures like nuns, and other such people, but if the local chieftains are not supportive, it is very difficult to implement anything. That is one thing we have learned, we must choose our partners carefully so that we will not be wasting too much time and resources in convincing resistant people. As we call it our multi-stakeholder approach, communities and the private sector are really a part and parcel of the uptake and sustainability of the project.

7. How does scale play a role in the projects?

A lot of projects came about in many areas in integrated waste management, which was an escalation. I would like to think that we were able to contribute, in a small way, to the synergy. When the whole country got used to ISWM and different organisations started working on it, we started to move out of the sector. We shifted to sanitation when the ISSUE 2 project came along.

8. What has been your journey and work done with WASTE in regard to sanitation?

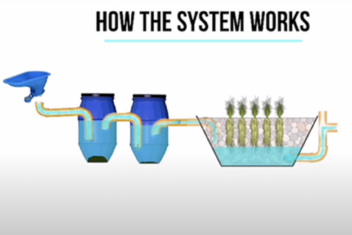

In the sanitation sector, we had a very old law which was just supporting the housing sector, focusing on the aspects of building septic tanks and plumbing infrastructure. Again on the learning part, septic tanks are not really designed for urban wastewater treatment. The ISSUE programme was for ecological sanitation, and that was very challenging. Because it is about dry toilets, the people had preconceived notions about it. Some people were convinced on the ecological aspects.

For the UWEP project our focus was the urban poor. For our initial local government, we had a pilot project that was not successful, but we learnt a lot. So when we went to another local government we used the learnings from the small pilot to implement a bigger project in another locality. The urban poor pilot faced many challenges in terms of logistics and government support, but in the rural poor—the agricultural villages up in the mountains—it could run on its own. Because in those rural poorer farming regions, the community knew the value of urine from traditional practices. It was successful there and even continued later. Many years later, even after we left, we found out the eco-san toilets that we had built were still functioning and in use.

A big part of what we did for sanitation was on advocacy. We were working in poor settings in urban and rural areas there is a lot of mortality in children because of bad sanitation. During 2008, the year of sanitation, sanitation became a big issue and we were able to link it with water and raise significant awareness. We also built a network, the Philippine Ecosan Network. This was a very influential and active network which had members from World Bank, UNDP and other organizations with whom we were able to join forces and advocate for bringing sanitation, especially for the poor.