Sustainability & partnerships: Tracing the history of WASTE’s inclusive approach to development cooperation

Diving back in history

WASTE and its partners around the world have been changing the development game for nearly 4 decades. We have together developed sustainable and inclusive solutions to many challenges in the waste management and sanitation sectors. Approaching the organisation’s 40th anniversary, we wanted to revisit some key players from our history of collaborations to learn lessons on how we can maintain the spirit of our founders and early work as we move forward.

The following traces WASTE’s history through three continents and many decades, sharing the stories of 7 pivotal individuals who have contributed to this spirit through our work together. These individuals and organisations have continued to share our spirit of inclusivity in everything they do.

A few key takeaways

- Through our holistic approaches, WASTE and its partners around the world have been working on the underlying concepts of ‘circularity’ for decades. It is only recently that high level discussions have rebranded and called more attention to the importance of what is called today “circular economy”. Circularity is integrated in our approach.

- Working with the informal sector is difficult but a critical component to sustainable waste management systems. All our partners echo that this aspect of the work as pivotal to the inclusion and innovative nature of their work.

- Institutionalisation of key concepts and approaches in policy, whether on local or national scales, are crucial for ensuring sustainability of our work.

- Buy-in from the communities, especially local leaders, can either catalyse the success of or be the sole reason for failure of interventions. We must ensure our programmes and solutions are co-created with and by the communities we are trying to serve.

- Real change and local ownership take time to have sustained impact. Our projects, ambitions, and relationships with key stakeholders, shouldn’t forget this key consideration.

Jump to:

- Billy Bray – Managing Director, WASTE Advisers Malawi, (Blantyre, Malawi)

- Pamela Kabasinguzi – Executive Programme Manager, Caritas Fort Portal-HEWASA (Fort Portal, Uganda)

- Victoria Rudin Vega – Director, ACEPESA (San José, Costa Rica)

- Rueben Lifuka – Managing Partner/Environmental Management, Social and Governance Specialist, Riverine Zambia Ltd, WASTE Zambia, (Lusaka, Zambia)

- Kulwant Singh – CEO, 3R WASTE Foundation (Haryana, India)

- Abhijit Banerji – Managing Director, FINISH Society (Lucknow, India)

- Dan Lapid – Executive Director, CAPS Philippines (Manila, Philippines)

Gamechanger 1: Billy Bray

Managing Director, WASTE Advisers Malawi

Blantyre, Malawi

“The result was that almost 95% of funding came to directly to Malawi, which is revolutionary for the international NGO industry.” What I loved about WASTE and the Diamond, was that development never had the approach of “what do you think” rather than “what you should do”.

WASTE Malawi started as a branch of WASTE Netherlands which was opened in Malawi in 2014. WASTE NL was looking into how to change operations to be more efficient in target areas. Most of the existing international and local NGO structures caused the perception that poor countries are used to raise funds to cover large overhead costs for international NGOs. WASTE wanted to do things differently and the Malawi office was a kind of pilot to see how it could be done. The approach was that WASTE MW are the implementers and WASTE NL can support and empower with technical advice. The result was that almost 95% of funding came directly to Malawi, which is revolutionary for the international NGO industry.

In 2019, we finished with a big EU project and were in the last year of a project with the Gates Foundation. At that point, we felt that WASTE MW could go completely autonomous. So, we opened a local branch and transferred all the assets and liabilities to the local NGO, with its own local identity and supervisory board.

1. What have you worked on with WASTE?

WASTE MW started with a focus on water and sanitation (WASH), engaged with development groups with a classic infrastructure style. However, we used the Diamond model developed by WASTE in implementation. Thereby, engaging with various players and local stakeholders, while trying to take the ownership of our problems there. This made it a model where we recognized the importance of infrastructure, while working towards developing and implementing the necessary framework to properly manage that infrastructure. In 2014, we had our first two major projects, and along with a few other smaller research projects. But it was the first two projects that helped us to position ourselves in Malawi, and now we are expanding into the consultancy role as well.

We started with an EU-funded project focused on three rural towns, with a component of schools, marketplaces and water included in it. After this, we had a project with the Gates Foundation which involved a public-private partnership (PPP) approach. From the beginning, we worked with the city council which was actively involved in the development of that project. The aim was to understand and meet their needs together. We successfully developed the concept with the city council and together applied for funding to jointly develop a value chain within the faecal sludge management system.

In total, we managed to put 44 public market toilets operated by the private sector, along with developing emptying associations and technologies with three decentralized treatment sites where the faecal sludge was collected. What wasn’t conceptualized in the beginning was the extent of demand for emptying services. The containment facilities within Malawi’s urban set-up were not very well developed. We later realized that the containment facilities were quite fragile. Based on this understanding, we diverted funds to improving containment facilities, aiming to generate more demand for the emptying associations. We have since developed around 200 extra pit latrines. Once the project gained some momentum on the ground, we as WASTE Malawi, would exit giving the stakeholders the freedom to continue it on ground. We have been able to develop a model where the cost of constructing the containment facilities is very low

2. Can you describe a little more about those projects and your work process with WASTE on them?

What I loved about WASTE and the Diamond, was that development never had the approach of “What do you think?” rather than “What you should do”. This helped apply their technical experience to come up with the best solutions for the local context, a consistency observable both in the Diamond and the branch approach. Following this helped us independently win contracts from the EU, BMZ, etc. Since I come from a business sector background, I was initially not keen on interacting with the NGO sector. WASTE supported me with understanding the concepts and value chain of the WASH sector to bring it all together

3. What were some of the key take aways and challenges that you encountered during the process?

The Diamond model creates ownership, something that we have witnessed. It is also now followed by the city councils, with more and more people taking to the concept of involving the private sector to help solve the problems in the sanitation sector.

The biggest challenge is time. This is especially because of the bureaucratic nature of government bodies which delays the process of getting an approval on contracts and documents. Thus, the Diamond is very good for ownership—but it can take a long time for true understanding and sustainability. Its follow ups and monitoring can be time consuming. Often, donors do not understand this. But when we look at the Diamond, a lot of the effort requires people with skills and capacity who can facilitate to be hired. This takes time and resources to facilitate the process, making it a major challenge, but one whose value is worth it.

4. Was the model adopted scalable later through the years?

I definitely think it is scalable, the process is scalable in the sense that other cities have just taken on from what happened in region that we were working in. However, another challenge that remains is that the lack of proper leadership opens avenues for corruption, since there the process involves delegated decision-making power. The local body should have strong leadership and integrity—attributes that are important for every business but specifically for the kind of development process that we are looking at.

5. Can you share aspects that didn’t work out? What alternatives did you adopt instead?

With one of our biggest projects, there was an issue with trust in the beginning. Although we develop the projects together, there often comes a time when you need to finetune and change some things. This can involve some leadership changes at the high level, thereby generating some suspicion on the ground. Thus, our first year of that project involved efforts to restore trust rather than making significant progress on its bigger aims. Importantly, because these facilitation processes require trust, we must trust that local councils want to do engage with a bona-fide attitude, while they must trust that the NGOs are not here to just push our own ideas to merely get business from them. It takes years to develop trust and only a moment to destroy it. It is one of our organisation’s core values to operate with trust

6. What do you think about the Diamond model from a business perspective?

We have a situation now for example, where one of our partners is very strong on the social and inclusion aspect, but if we talk about sustainability, we can’t have a hundred percent approach form day one as the money has to come from somewhere. So for this specific project we tried to balance it, by starting to serve the city, but we couldn’t be totally inclusive from day one. We would have to start skimming a few of the middle-income markets and then move downwards and find additional revenue streams to try and cover the bottom spectrum. Highlighting the issue to the governments at those of levels, because some aspects of sanitation cannot not have a completely linked business model. We cannot have a completely independent business model to reach everybody. Subsidies are required for some and someone else must pay for some parts.

In some areas, we cannot expect someone to make the containment facility and to pay that loan back with interest, because they didn’t have money in the first place to do it, otherwise they would have emptied it. Their disposable income is too low to start thinking of that kind of long term process of loan repayment, and thus would not work. What is required is to increase the general disposable income, and raise the poverty level a bit. If we increase the disposable income and there is no business model at that bottom end of the range, then we would require cross subsidies to make the model work at that level

7. How does WASTE Malawi work with the government?

It is probably more invisible, where we have started to look at high level government engagement. Where we first took the lead on this was in regard to compost subsidies. We realized that to create value and to complete the value chain of faecal sludge management (FSM), we had to bring organic waste from the markets, thus making solid waste management (SWM) an important part of value creation at the end. We also noted that in the process of emptying our pit latrines, there was a lot of solid waste there, so it was almost impossible to separate the two. We were able to start creating compost at the end.

Compost was a real game changer for us at the industry. Since 2006, Malawi has been running very heavy fertilizer subsidy programmes started by the government to stimulate economic growth. The fertilizer subsides helped initially, because it boosted crop yields from 1 to 2.5 tonnes. There was no stewardship of that fertilizer and no model of how we could improve our soils. Thus, following the last twenty+ years of this heavy fertilizer programme, and then the FAO raised the issue that our soils were below critical levels on carbon and that yields had dropped to pre-subsidy levels. It was all going down, and the government could not pull out of the subsidy program as then nothing would be left. Our approach was to ask the government to start subsidizing compost rather, that way they would be subsiding the cleaning up of the city and the end product to go back into the soil. Compost helps the farmers restore soil quality, rather than just farming on sand with fertilizer. We knew getting the government to subsidize compost would increase the momentum for our whole value chain. We are the biggest compost producers in Malawi, we have standards, and have been discussing with governments at all levels. We also engaged with a research institution to get an economic impact paper together, with which we can use to show the government the impact of shifting some of our subsidies.

8. In your opinion, what is the future of the Diamond?

The Diamond is a philosophy that is bigger than the Diamond. The philosophy treats people as equals with an opinion and then gets them involved in the process of development. The philosophy is really bringing people together and giving that kind of importance, recognizing that all their opinions matter, and understanding how they want products to be developed and services to look like. In that sense it is a philosophy of development, rather than just a project implementation tool. So, 10 years from now, the philosophy of treating people as equals will always be around. In the development world if you just look at the psychology of it, the mentality– called transactional communication theory—where you speak to someone as equals, works best. As NGOs, we have to talk about equal terms and come as equals when we are working.

What I find valuable of our Netherlands office is that we are very functional in our day to day working. We try not to ‘reinvent the wheel’ each time. When we come up with something, we share it with the Netherlands, and having an international body that can move around and see the various kind of activities that are happening, connecting as a learning center that can share information of drivers on the ground, see how this work will be in different contexts, is a very important function.

Gamechanger 2: Pamela Kabasinguzi

Executive Programme Manager, Caritas Fort Portal-HEWASA

Fort Portal, Uganda

“With WASTE, we have ventured in into an area where there were no people and there was high risk. Together, Caritas Fort Portal-HEWASA has developed expertise in a niche that adds value to the work, making us different and capable to partner with other organizations…While others talk of households as beneficiaries, we talk of the households as clients who are able to buy a product and make decisions for themselves.“

Caritas Fort Portal-HEWASA is the social services arm of the Catholic Diocese of Fort Portal. It was established in 1980 as an emergency and charity organization to support people affected by the civil unrest at the time. In 1993, the organization expanded to include water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), justice and peace, agriculture development services (ADP), and financial services.

1. Can you describe the thematic focus of your organisation?

Caritas works a lot on water, sanitation, hygiene (WASH) and health, along with a focus on agriculture, microfinance, and livelihood programmes which are based in the refugee camps along with gender issues. We work on water for drinking and for crop and animal production.

We have done a lot of pipe water systems in the western region of Uganda, contributing to the construction of over 50% of the water systems [there]. Caritas has also been the main regional coordinator for all of the NGOs working in the western region on WASH. We have been working to build capacity of several other organizations. We have also had several development partners to support this work, including UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund), WaterAid Uganda, German GIZ (Gesellschaft fuer Internationale Zusammenarbeit) and many others.

2. When did you start working with WASTE?

Our first programme with WASTE was in 2011, where we were coordinating partners in the WASH Alliance. Together, we focused on sanitation and looking at public places like commercial buildings and markets and introducing financing for WASH. WASTE’s Diamond approach was introduced as a multi-stakeholder way of developing the local sanitation market and businesses.

We started with WASTE’s Diamond approach by training local stakeholders and introduced it to financial institutions such as HOFOKAM, which is an institution formed by the Catholic Church and has 3 dioceses within it, forming a microfinance body. Since at that time there were very few institutions interested in working with and giving loans for sanitation, we worked with HOFOKAM to introduce how a sanitation loan product would work and be interesting for them. Given the relatively new nature of the loan, we set up a Guarantee Fund to support the early initiative. WASTE helped us in capacity building of the staff in financing, product development, business identification across the value chain in sanitation, marketing skills, business skills, how to market the product in terms of sanitation technology options, and how to approach the clients.

Now under the new FINISH (Financial Inclusion Improves Sanitation & Health) Mondial programme that we are working on with WASTE and other international and national partners, we see that we have picked up exactly on where the WASH Alliance had stopped. Since there was already some work done in the region where we are based, there was some awareness amongst people about sanitation and businesses that were working on this. Caritas is now leading on the local financing, business development, (what we call the supply side of the Diamond approach). We have thus been building a system where there is some sustainability.

So, with WASTE, we ventured in into an area where there were no people and there was high risk. Where people were saying “How can you expect an average household to afford a permanent sanitation system, given their low incomes?” But we have been able to produce results and develop the local market, due to our partnership with WASTE, to work on this risky issue, where most NGOs would not go. Together, Caritas has developed expertise in a niche that adds value to the work, making us different and capable to partner with other organizations.

3. How do you integrate WASTE’s Diamond Model in your work on the ground?

It can be difficult to explain how the Diamond approach is different. We must take time to explain how we work with the government, households, financial institutions and entrepreneurs together. Most NGOs give subsidies or reduce interest, but that does not help address the problem fully. Instead, what we do differently is focus on high demand creation and emphasize the financing part of the Diamond. We approach the financing part from the angle of business, financial literacy, and market creation. While others talk of households as beneficiaries, we talk of the households as clients who are able to buy a product and make decisions for themselves.

What is unique with the Diamond, is that the four stakeholders are brought together and function in a linked manner. All corners must be developed together.

4. Can you share any challenges met with the Diamond and how you overcame them?

Some challenges arise with financial inclusion and leaving some poor households behind. For situations like child-headed households, we look at merry-go-round and other group formation schemes. These take time, but it works for people who cannot afford to build a toilet on their own. Another challenge is that some people have already constructed basic toilets, and we come in with improved technologies, but these people have already spent money. In such situations, we support in improving what is existing, by making sure that they have more sustainable toilets, for example, with washable floors.

Another issue is that once a leader of a community thinks that they cannot afford, then if becomes a major challenge. We try to work in areas where the leaders are positive and want to work with us. Finally, another challenge was for the bank itself—a financial institution could not have it in mind that people would want a loan to construct a toilet. It takes a lot of time to develop the whole system properly.

5. Was the model scalable?

When we are looking at scalability, I consider scale at different angles. One is scaling with the number of systems (toilets) built. Another is scaling the approach, so when we work with other organizations, such as community-based organisations (CBOs), we train them in the approach to take up the roles of supply and demand. Another way of scaling is through changing the way we finance projects, for example through result-based financing

6. Did the models adopted require any fundamental changes later?

The areas where the model has not worked well is where there is no assured income in the community. Where it worked successfully has been regions where there are for example, banana plantations, and people have some form of income. To me, in the first years of using the Diamond approach, we did a lot on demand creation and government engagement, but the business and institution part of it was not very well emphasised. While demand creation is good, what makes the sustainability and scale is the other two pillars of financing and business development.

7. Can you share why others should work with faith-based organisations like Caritas?

What is unique is that Caritas is a religious organisation. It has unique approaches and looks at the holistic person. It looks at charity of course, but it works to develop a person in all spheres. When we are doing demand creation, we use the platform of the Church because people believe in their leaders, they believe in their priests, their sheikhs, and in what they do. Even the Pope talks about the environment and the dignity of man while referring to the Bible and the quotation where every household is asked to be kept clean that, “When the God comes to bless you, the house should be clean”. Even the Quran and other religions have similar kinds of scriptures. We are working with other religious institutions. Research has also shown that religious institutions can activate people to work beyond what other mediums would push them to do. We, at Caritas, are using a similar approach to encourage people towards quality-of-life improvements like safe sanitation.

Gamechanger 3: Victoria Rudin Vega

Director, Asociación Centroamericana para la Economía, la Salud y el Ambiente (Central American Association for Economy, Health and Environment, ACEPESA)

San Jose, Costa Rica

“The Integrated Sustainable Waste Management (ISWM) model itself considers circularity at its core, but now everybody is talking about the ‘circular economy’. We are learning more about it, because…it is an issue linked with climate change and deals with the design of products, not just the management of waste.”

*Asociación Centroamericana para la Economía, la Salud y el Ambiente (Central American Association for Economy, Health and Environment, ACEPESA) started working on solid waste management in 1991.

1. What is the thematic focus of ACEPESA and what kind of projects you are currently working on?

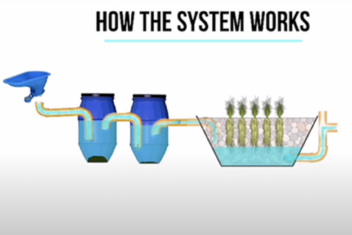

The thematic focus of our work is integrated solid waste management, water, and sustainable sanitation, linked to climate change adaptation and mitigation, all related to local economic development. Some projects we are currently developing refer to the improvement of municipal composting processes and products, (organic waste treatment and fundamental for mitigating greenhouse gas (GHGs) emissions. We are also working on the inclusion of informal waste pickers in municipal waste management systems, strengthening community water systems, and the promotion of alternative systems for wastewater treatment, through constructed wetlands.

2. When and for what projects have you partnered with WASTE in the past?

We started working with WASTE in 1996 on Latin American research on waste management in micro- and small enterprises and cooperatives. Since then, we have partnered to implement the Urban Waste Expertise Programme (UWEP), then in ISSUE 1 and 2 projects. We jointly implemented a project for WEEE (Waste of Electric and Electronic Equipment) Management with funding from the Costa Rica-Netherlands Bilateral Agreement.

3. Can you describe a little more about your work process with WASTE?

We worked in a very well-coordinated way. WASTE contributed significantly to our development as professionals in the field of solid waste, introduced us to networks with other organisations. We also worked together on the development of technical materials. There was always clarity and transparency. Specifically, the focus of the UWEP project was on the municipality of La Ceiba in Honduras. ACEPESA had the role of coordinating and providing assistance to local partners who oversaw implementation on the ground. In turn, WASTE supported the cohort with technical assistance and capacity building. In ISSUE, the dynamics changed a bit as the emphasis was on sanitation, which was something totally new for us. There, WASTE was fundamental. This pushed us to work on sanitation, an issue that, to this day, is central to ACEPESA. Similarly, with WASTE’s technical support, we learned from the Netherlands’ experience in WEEE management, which propelled us as one of the leading countries on the subject in Latin America.

4. What were some of the key take aways for you and ACEPESA from that early collaboration?

A fundamental element that always guides our work in waste management to date is the Integrated Solid Waste Management (ISWM) model, which we were privileged to learn directly from WASTE’s co-founder, Arnold, along with the other founders. Prioritising the informal sector is another lesson that continues to motivate our work. Similarly, we continue to promote the sustainable sanitation approach. It is here that we find the main challenges, as we initially met more resistance to its implementation than in more traditional approaches. Another key learning was to work collaboratively with other organisations, to learn from others, and to drive change together.

5. How does the informal sector play a role in your work?

There is a regional project for all Latin America working on informal sector inclusion, it is called Latitude Aire, funded by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Coca-Cola amongst others. Now they are supporting some big activities and projects in Central America and the Caribbean to find how to get local governments to integrate the informal sector into the municipal process. For example, what the municipalities understand sometimes from our own solid waste law from 2010, is that they must do the recycling themselves, and thus, usually avoid the existence of the informal sector entirely. So, we are working with municipalities to integrate the informal sectors, especially in the collection and segregation process of waste management

We do not have sufficient data regarding the people who are working informally. So, it is difficult to know who and where they are.

6. Was the Integrated Sustainable Waste Management (ISWM) model adopted scalable in your work?

ISWM was adopted as an approach in the formulation of the country’s municipal waste management plans, so I would say yes. We were responsible for formulating the manual (with support from GIZ (Gesellschaft fuer Internationale Zusammenarbeit)) that guides the process. In terms of sustainable sanitation, thanks to our work, constructed wetlands are widely accepted in the country and throughout the Central American region.

7. What aspects did not work out on the ground?

In the case of the UWEP project mentioned before, it was not possible to follow up the implementation of the project in Honduras due to the distance. At that time, it was not easy to set up remote communications. In the case of Honduras, a factor that was always a constraint was the changes and influences of local politics. In terms of sustainable sanitation promoted within the framework of the ISSUE project, there was no social acceptance of dry toilets as there is a strong culture of using water for cleaning. Experiments with the collection and storage of human urine were started, which seemed to us to be a critical issue. However, we did not get the institutional support to be able to continue developing the experiences.

8. What do you think about the aspect of circularity in this work?

The ISWM model itself considers circularity at its core, but now everybody is talking about the ‘circular economy’. We are learning more about circular economy, because for instance in a place like Costa Rica it is an issue linked with climate change and other such topics, and deals with the design of products, not just the management of solid waste.

The concept of circularity is also more asked on the ‘high’ government and private sector levels. But the people are more concerned with direct issues of sanitation, wastewater, what do they do with waste and other such visceral issues. In Costa Rica, the issue of climate change is more in focus.

9. What are your thoughts on the future of the waste management sector?

Solid waste will remain a critical issue. We have been working on plastic pollution and marine litter since Costa Rica has two oceans. We must deal with both. We must find solutions to treat the waste that is recovered from the seas and rivers. We do not have solutions right now. Some people are sending it to cement factories, but there are few solutions and approaches to deal with this issue currently. Electronic waste is another issue that is relevant for us. We have made some progress but still there is a lot more to do. In the past, municipalities did not want to engage with organic waste and preferred to send it to landfills. But over the last few years, because of rising costs, they want solutions for treating and managing organic waste better. We have been working on building a national strategy for treatment and management of solid waste, linked with climate change [mitigation and adaptation]. So organic waste is also a critical issue today.

Gamechanger 4: Rueben Lifuka

Managing Partner/Environmental Management, Social and Governance Specialist, Riverine Zambia Ltd, WASTE Zambia

Lusaka, Zambia

“We engaged the community groups themselves by going down on the ground and looking at the challenges that they were facing and talking through possible solutions. So we are not walking into a community with a ready-made package. We are essentially saying look at the options and let’s co-create this together.

1. When did you start working in waste management and what is the thematic focus of WASTE Zambia?

When we started with the activities of WASTE in Zambia, it was in collaboration with my company Riverine Development Associates, and we did a couple of projects. The big one was the ISSUE 2 project which was about improved sanitation in Kabwe. We also did work around the economic aspects of the informal sector in waste management. We looked at how they were adding to the waste management system. Subsequently, a decision was made to work with one or two local NGOs and then finally, WASTE Zambia was established. Whenever possible, the team from WASTE Netherlands and we shared notes together and still maintain that informal connection.

2. When and for what projects have you partnered with WASTE?

We have worked with WASTE NL around the bigger issues of integrated solutions to waste management and on the economic aspects of the informal sector in waste management. The earliest project was around the whole thinking about innovative ways of improving community waste management. We started with a conference in Dar-es-Salaam, from where our partnership with WASTE NL began.

We had done some work in the central province and were looking at improving sanitation in a particular community, the largest informal sector community in the town. The idea of ISSUE 2 was to be innovative and find mixed solutions for sanitation and waste management, a provision for a peri-urban area. That helped us innovate by introducing ecological sanitation. We looked at how to introduce ecological sanitation by linking it with waste collection mechanisms of municipal waste. That opened up the authorities’ minds about how they could provide sanitation which is relevant to the area. It was a very transformative and innovative approach at the time. This started in May 2007 and continued until 2009.

We have now upscaled some of the pilot activities we conducted in Kabwe. Around 2012, we worked together to develop the municipal guidelines for the Republic of Botswana. This was a UNDP-funded project. We traveled to Botswana and understood how they put value to waste, the valorisation of waste, and developed systems to strengthen the municipal guidelines.

In 2014, we had a big conference in Egypt looking at circular economy. We were invited by the colleagues at UNDP and the government of Egypt as a part of the collaborative working group. We held an expert workshop on circular economy and resource recovery. We were a big publication, because at that time, WASTE was given the opportunity by UNEP to contribute to a major publication. Lusaka was one city that was selected in the publication to be covered.

3. What were some key takeaways for you from the early collaboration?

If I take the mixed solutions project at Kabwe for example, we looked at it at different levels. Firstly, as experts within WASTE Zambia and other countries, we had many detailed kick-off meetings. So, there were many days of really sitting together, going through the concepts and understanding the different limitations, modifying the model, and talking through how we could bring on board the different stakeholders. We discussed not only technical solutions, but also the engagement approach and other such ideas as part of the bigger system. Coming on the ground we did exactly that. We engaged the local authorities, the elected councilors, the technocrat side, the local government to explain what we were trying to do, and we engaged the community groups themselves by going down on the ground and looking at the challenges that they were facing and talking through possible solutions. So we are not walking into a community with a ready-made package. We are essentially saying look at the options and let’s co-create this together.

4. What were some of the challenges encountered?

Like in any project, some of the obstacles faced were the resistance to change. Not everyone would warm up to a new idea simply because you have come and said it works. They have been used to doing it in a particular way. The concerns about things such as health, fielding questions like Where are we going to be placing our collection container? How frequently is removal going to be done? How hygienic is that? All those questions were asked, to a point that we then had to put in a mechanism to bring the elected councilors from the capital to look at the ecological sanitation (Eco-San) toilets that had been constructed in Lusaka to talk to the people firsthand, learn lessons, and then go back to be ambassadors in their communities. So, the resistance to change is always there and has to be overcome slowly.

In certain aspects, the uptake of innovative ideas can be constrained by the absence of appropriate policy measures [or restrictive ones]. Engagement with different stakeholders, consulting them, getting buy-in to the project and getting their ideas on how the ideas can be refined, was the approach we took, but it takes time.

5. Did the model prove to be scalable and sustainable?

The work we did on the economic aspects informal sector in waste management also influenced the thinking of the Zambian Central Government in policy formulation. What we did has been looked at to understand how best the policy measures and structures can work to take the informal sector on board.

For the mixed solutions, the WASTE Zambia has been working towards replicating some of the mixed solutions to sanitation and solid waste management to other parts of the country, including the capital city, Lusaka. So the impact has gone beyond just the central provinces and is something that is being looked at in other parts of the country.

Gamechanger 5: Kulwant Singh

CEO (Chief Executive Officer), 3R WASTE Foundation

Haryana, India

“Things do succeed ultimately, despite challenges, where there is persistent effort and time.“

1. When did you start working in this field?

I have been working in the urban sector for nearly three decades. I was Executive Director of Human Settlement Management Institute New Delhi from 1992-03. Subsequently, I joined UN-Habitat in 2004 and continued until 2015 as a Regional Advisor for Asia and the Pacific with a focus on implementation of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), particularly in the field of Water and Sanitation. 3R WASTE Foundation was established in late 1996, and our cooperation with WASTE Netherlands has been since beginning.

2. Can you describe the thematic focus of 3R WASTE Foundation and the kind of projects you are engaged with currently?

Our role has been largely a knowledge partner. As such, we have been focusing on capacity building, training programmes, and research and documentation. We started working in the field of sustainable waste management, and there was a lot of learning that we had from WASTE NL to start. we started learning the kind of model that WASTE has developed of working with different partners for the Integrated Solid Waste Management (ISWM) model. With this, we followed the route that WASTE laid down, which involved interacting with different local stakeholders such as the local governments, businesses, banks & financial institutions and communities, amongst others.

Another key area where we have been working is in plastic waste management, where WASTE NL colleagues have been majorly involved. There were a couple of initiatives that were taken up in India. One major initiative, in partnership with our sister organization called FINISH (Financial Inclusion Improves Sanitation & Health) Society, was where we partnered on a plastic waste management project in Udaipur, Rajasthan.

3. When and for what major projects have you partnered with WASTE?

Since we started with 3R WASTE Foundation, we always had a close relationship. One of our major partnerships was relating to a research project covering around 10 cities—5 from Africa, 1 from Nepal and 4 in India. As far as India was concerned, 3R WASTE played a key role in implementation. The focus of this project was to find ways we could somehow manage to create value from waste, including septic waste management.

The four cities we worked on together included Dungarpur (Rajasthan), Warangal (Telangana), Trichy (Tamil Nadu), and Pune (Maharashtra). This research project was very interesting, and we enjoyed working together. Of these four cities, Dungarpur was a small city, in Rajasthan. This city of Dungarpur had a small population of about 60-70 thousand people. The city did not have any sewerage facilities. The city municipality was managing the septic waste as well as the green and dry waste. The city did wonderful work in these areas. I would say that we helped improving the city in many ways. Over 2-3 years, the city improved managing its waste significantly. Dungarpur ultimately became a role model for the country. Specifically, because India has around 2,000 cities which were of the same size and had similar problems, so the model could be replicated.

In partnership with WASTE NL. we have also been working with other national and international organizations such as RDO Trust, USAID, UN-Habitat, and UN Centre of Regional Development in Japan.

4. How does scale play a role in the work 3R WASTE Foundation is doing?

Largely we have been working at the local level when it comes to waste management. We have been working with local governments and small players. Today, scalability is being facilitated with Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funding. Along with that, when you look at the current FINISH Mondial programme, today it is operating in different countries across the world, but it started on the local and micro-level in India (in 2009). So, scalability of the ISWM model and then the Diamond approach has been accelerated greatly from the work here and under FINISH Society.

5. Did the models require any fundamental changes later?

In India, waste is dealt with at a national level by various ministries and departments. At the national level, responsibilities are mostly related to policy-making and action plans. At the state level, the responsibilities are pretty similar, but implementation falls on the shoulders of the local governments. When it comes down to implementation at the city and rural community level, it comes down to just the local governments, and there is where the real challenges lie.

Often, local governments do not have enough manpower, strong institutional framework, and knowledge of technology. It is also a challenge to link all these levels of national, state and local frameworks. However, we have received a lot of support on the national level in the past years, and that has helped to really enable us to support many cities to do better in waste management. This has also pushed for a framework of handholding between the cities, leading to a city-to-city cooperation framework developing both intra and inter-state cooperation. WASTE has really been helpful in bridging the gap between the private sector and governments, along with the other players. While working with the ISWM model, we had to customize it to the local needs. The principles stay the same, but the application must be customized according to the local needs and context.

6. Can you tell us a little about aspects that didn’t work out on the ground? How did you overcome these hurdles?

We have met many challenges, specifically when it came to implementation. There is a significant role of the informal sector in waste management. Waste collection and segregation is done largely by the informal sector—those people who do not have any regular source of income. Problems come often with the use of technology. The application of technology becomes especially important, but often human resources are not available to operate that technology. Those are the kind of difficulties that we have faced while working in India. But things do succeed ultimately, where there is a persistent effort and time.

In one project, we felt that we could combine septic and waste management, but it just did not work. For example, we were working in the city of Pune, where we found that within the same municipality, there were two parallel departments to address. There was an engineering department dealing with sanitation and building the sewerage systems. Then there was a department dealing with waste management, both within the same municipality. These two departments were running parallel and were not even talking to each other. So, we thought of bringing them together on the same platform to coordinate, but it was not possible. In the end we had to leave it at that. Finally, we addressed both problems separately and tried other solutions. So, we had to customize many things and understand the ground realities that were quite different than we envisioned from the beginning.

7. What is your vision for the future?

The future is bright. As partners, we must work together to address these problems and issues in different countries. We will certainly need to make use of these processes and technologies that have been developed over the last years. Today we are not just talking of integrated solid waste management, but of circular economy. The circular economy principles must be really integrated into our overall approach. The processes must also accordingly be adjusted, and application of new technologies be brought in. In any case, waste management will remain a critical issue and we will be there as partners to address all new challenges.

Gamechanger 6: Abhijit Banerji

Managing Director, FINISH (Financial Inclusion Improves Sanitation & Health) Society

Lucknow, India

“We have had so much of freedom in designing and implementing the programme, and I always believe very strongly that the reason behind the success of this program has been the flexibility and trust that we have had and enjoyed with WASTE.“

*FINISH Society was established in 2010 as part of the sustainability strategy of WASTE’s first FINISH programme.

1. How long have you been working in sanitation and waste management?

Through our partnership, we have built our technical capacity and our approach of how the sanitation market can be serviced. It is from there that we evolved into other segments such as school WASH, waste management, household sanitation, etc. The core approach applied is the same as that of WASTE NL. The model we follow is an ‘eco-system’ approach. We try to keep operating costs low, leveraging funding and resources from other players.

We began the first waste management programme in 2014. We started with the municipality of Udaipur, by helping them improve the sanitation situation. They liked the commitment of our team and how the team was delivering on the sanitation portfolio. We were further discussing the waste management issues of the city together. With the high level of commitment of the team, our work further translated into multiple projects with different municipalities around India (i.e. Udaipur, Dungarpur (Rajasthan), Gaya, and others in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Orissa and Bihar). That is how we gradually got into this and other relevant sectors that we are working on.

2. What is the thematic focus of FINISH Society?

Ever since India was declared open defecation free (ODF), there has been a lack of support and grants for nonprofits working on sanitation. Given this business environment, we expanded our portfolio to include waste management as well. At present, we are particularly focused on wastewater treatment because very little grey water is treated in India, making it an area of high importance for the future. Also, the Government of India is focusing on the Jal Jeevan mission. This focuses on providing access to drinking water and given the scarcity of such, wastewater treatment will become an important tool towards achieving these national development goals as well.

We also did two wastewater treatment projects for the municipality in Dungarpur earlier. We are currently focused on a similar one for The Nature Conservancy in Chennai, where we have designed a large plant for TNC. The idea is to treat about 7 million liters of water every day with an aim to make the water of the Sembakkam Lake usable soon. Interestingly, the technology that we are using for this project is focused on planned constructed wetlands, something that we picked up from WASTE. We use this, combined with a mix of other technologies, making this model both low maintenance and low on capital and operating expenditures.

Our current idea is to develop a vertical for nature-based solutions (NBS) while gradually building our own capacities and understanding of the market. The other vertical is on skill training and livelihoods, looking at the adverse effects of COVID-19, especially in terms of employment and economic development.

3. How do you see scalability in your projects? Is it only geographic or are quality and sustainability also key considerations?

Quality is paramount. Ever since we began, the unique selling point (USP) of our sanitation programme has been the safely managed aspect of sanitation. We continue to strive for that. A similar focus is there for other projects, and I suppose that is the reason why clients that have worked with us in the past continue to work, support, and expand with us. The quality focus is essential, something which the Government of India also recognized, making us a Key Resource Training Centre (KRC) for the purpose of sanitation. With quality, we also try to attain scale, as a certain amount is required to reach economies of scale. This is key since our ambition is to keep facilitation costs low and create bigger impact.

4. Could describe your process of our collaborations?

The best part about FINISH Society’s partnership and relationship with WASTE has been how we work together. We have had so much of freedom in designing and implementing the programme, and I always believe very strongly that the reason behind the success of this program has been the flexibility and trust that we have had and enjoyed with WASTE. At the same time, whenever there was a need of assistance and support in terms of capacity building, discussions, working out solutions, or looking for new partnerships, we have always had excellent support.

I believe we have taken up an approach like that of WASTE in the work and also as an organisation. There is a lot of focus on trust between the team members and partners. Today, we are glad that most of the people who joined the organisation have stayed with us, with most being associated with us for at least four or more years. This is great considering that we only became fully functional in 2012. Thus, we have all stuck along and grown, and done well together, making it a good ride so far. In the Indian NGO sector is particularly unique, given the case of high potential people who have received other offers. While some people have of course left to join much bigger brands and companies, but there are many who have preferred to stay. The team is happy and proud to work with the cause and the organisation.

5. What are some alternative approaches to WASTE’s Diamond model that you have adopted?

While the bedrock is the Diamond or the ecosystem approach where we try to integrate everything, a lot also depends on the ground realities and situations. This dictates how the model can be customized. Thus, a lot of freedom is also given to the team on the ground to decide what works best there. Just like WASTE has supported us, we also try and support the teams on the ground in a similar manner by giving them the freedom to see what will work best in their area, while providing them with backend support.

6. What are some of the challenges that you face with this work?

One of the challenges includes the operational issues which a small organization like ours encounters. There is always a challenge of managing a large programme spread across different states, while at the same time, managing the human infrastructure behind it. For example, our teams are today spread across 12 states. Managing these teams and providing them with support can be quite challenging at times. Further, one of the biggest challenges for us while expanding the projects is getting a good quality manpower, especially since we have this dichotomy—our pockets are limited but we are looking for quality manpower, making it a difficult balancing act.

7. What do you see for the future of this work?

I see a lot of opportunities together, one of which is the possibility of working on health infrastructure. For me it is the model of how we can leverage commercial financing and support that with grant for a social good. This model can be used in many ways, such as for improving drinking water, on municipalities or waste management enterprises and infrastructures. India is a huge market, and we have been able to build a team and culture which should last and deliver results.

Gamechanger 7: Dan Lapid

Executive Director, Centre for Advanced Philippines Studies (CAPS)

Manila, Philippines

1. What sectors were you working in, and can you describe your journey with WASTE?

The Centre for Advanced Philippines Studies (CAPS) was focused on research, with a vision to help the government analyse things. During those times, the Philippines was recovering from the effects of martial law, and we wanted to help. CAPS was like a think tank working on economy, politics, governance, and environment.

It was in the early 1990’s when we got to meet WASTE. After that, our work became more focused on waste management. In the early ‘90s, we were doing documentation research for the UNDP, World Bank, etc. on recycling and composting. We were part of the UWEP programme, and then there was UWEP 1, 2 and UWEP+. After this there was the EcoSan (Ecological Sanitation) ISSUE 1 and 2 projects. So that is how we started together. We were doing research on urban environment, specifically on solid waste management, and then later when UWEP and ISSUE came we also did projects on the ground. We worked with WASTE’s co-founder, Arnold, who was a very professional and good man, and I learnt a lot from him. He was very kind and generous with his time and knowledge.

2. Can you share a little more about the projects?

The Issue project was on ecosan, but the UEP programme was on solid waste. WASTE was able to acquire projects funded by the Dutch government. Issue and UEP both were funded by the Dutch government and it was WASTE that conceptualised the whole programme, and since they knew me they got me as a partner in the Philippines. To implement the programme. Thus we diversified the focus of work being at our organisation from research to also implementation partners on the ground. The model that we were using for the projects was the ISWM model primarily.

3. How did you work on the ground in these projects?

Before CAPS, I was working in the private sector. I do not have a degree in Environmental Science, I am sociologist. So the Integrated Solid Waste Management (ISWM) concept, approach and the technology were really new to me. I was really learning on the job and I learned a lot about the urban environment, integrated and sustainable solid waste management and such things. I can, to an extent, also say that because of my engagement with WASTE, I sort of became very environmentally conscious. It came that people started to call me an environmentalist. So the environmentalist piece and approach that I developed throughout my engagement with WASTE carried with me through the work I did over the years. People were noticing it until 2014-15 when we eventually closed the organisation.

4. Did you face resistance to the way of working the ISWM promoted?

Prior to the year 2000, integrated sustainable waste management was only in the minds of a few. Very few people were focused on recycling, composting, etc. It was not in the popular mindset. In the UWEP project, we did the promotional advocacy and also networking with many organisations and the government. Somehow, we were able to generate interest. We were able to connect and identify the players such as the formal and informal organisations and link up with them. This, in turn, became beneficial as we were able to develop our own network to sustain us later. As it became more popular in the minds of the people, in 2003 Philippines adopted a law on ecological solid waste management and we were a part of the network that assisted the legislative congress to craft the law.

5. How was the law developed, implanted and enforced in the Philippines?

The law was enacted in the early 2000’s but implementation was very difficult. Everybody was experimenting with setting up the segregation and putting up material recovery facilities and other such infrastructures on the ground. While the Department of Environment was very supportive, there were still concerns that would arise from the other departments and branches of the government. Many things were achieved in terms of segregation, where a lot of dump sites were closed or transformed into segregation centred where they would tap methane gas out of it to produce electricity. So there are many positive movements, but still there is still more to be done.

6. Can you share some challenges encountered in the work?

The biggest challenges that we encountered during the implementation of the programme was not just the government bureaucracy and the system, but also the local people. Many times the people themselves would not cooperate. It also depends on the mayor and the local chief, if they are aggressive in implementing change, then the local people follow. Otherwise, it is very difficult. You need these local champions for people to look up to and follow in order to implement and adopt such practices on the ground.

There are many civilian champions such as students, religious figures like nuns, and other such people, but if the local chieftains are not supportive, it is very difficult to implement anything. That is one thing we have learned, we must choose our partners carefully so that we will not be wasting too much time and resources in convincing resistant people. As we call it our multi-stakeholder approach, communities and the private sector are really a part and parcel of the uptake and sustainability of the project.

7. How does scale play a role in the projects?

A lot of projects came about in many areas in integrated waste management, which was an escalation. I would like to think that we were able to contribute, in a small way, to the synergy. When the whole country got used to ISWM and different organisations started working on it, we started to move out of the sector. We shifted to sanitation when the ISSUE 2 project came along.

8. What has been your journey and work done with WASTE in regard to sanitation?

In the sanitation sector, we had a very old law which was just supporting the housing sector, focusing on the aspects of building septic tanks and plumbing infrastructure. Again on the learning part, septic tanks are not really designed for urban wastewater treatment. The ISSUE programme was for ecological sanitation, and that was very challenging. Because it is about dry toilets, the people had preconceived notions about it. Some people were convinced on the ecological aspects.

For the UWEP project our focus was the urban poor. For our initial local government, we had a pilot project that was not successful, but we learnt a lot. So when we went to another local government we used the learnings from the small pilot to implement a bigger project in another locality. The urban poor pilot faced many challenges in terms of logistics and government support, but in the rural poor—the agricultural villages up in the mountains—it could run on its own. Because in those rural poorer farming regions, the community knew the value of urine from traditional practices. It was successful there and even continued later. Many years later, even after we left, we found out the eco-san toilets that we had built were still functioning and in use.

A big part of what we did for sanitation was on advocacy. We were working in poor settings in urban and rural areas there is a lot of mortality in children because of bad sanitation. During 2008, the year of sanitation, sanitation became a big issue and we were able to link it with water and raise significant awareness. We also built a network, the Philippine Ecosan Network. This was a very influential and active network which had members from World Bank, UNDP and other organizations with whom we were able to join forces and advocate for bringing sanitation, especially for the poor.